What is osteoarthritis?

Watch our video about what osteoarthritis is

Click to watch our short animation to find out what osteoarthritis is, what the treatment options are and what you can do to help yourself.

Watch this video with other language subtitles

| Waa maxay cudurada xanuunka kala-goysyada? | Somali subtitles |

| ઓસ્ટિઓઆર્થરાઈટિસ (Osteoarthritis) એ શું છે? | Gujarati subtitles |

| முடக்கு வாதம் என்றால் என்ன? | Tamil subtitles |

| اوسٹیو ارتھرائٹس کیا ہے؟ | Urdu subtitles |

| Beth yw osteoarthritis? | Welsh subtitles |

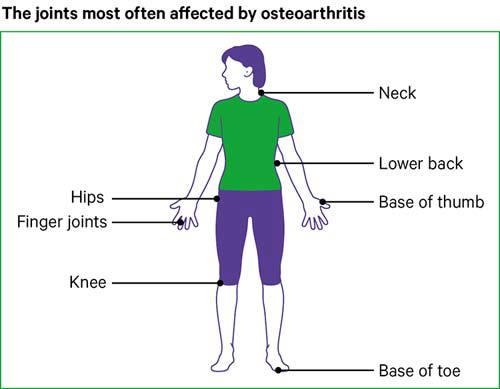

Osteoarthritis is a very common condition which can affect any joint in the body. It’s most likely to affect the joints that bear most of our weight, such as the knees and feet. Joints that we use a lot in everyday life, such as the joints of the hand, are also commonly affected.

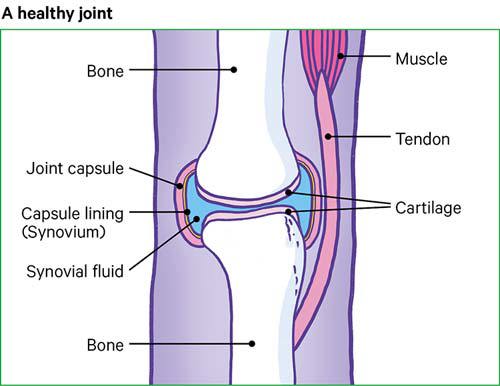

In a healthy joint, a coating of tough but smooth and slippery tissue, called cartilage, covers the surface of the bones and helps the bones to move freely against each other. When a joint develops osteoarthritis, part of the cartilage thins and the surface becomes rougher. This means the joint doesn’t move as smoothly as it should.

When cartilage becomes worn or damaged, all the tissues within the joint become more active than normal as the body tries to repair the damage. The repair processes may change the structure of the joint, but will often allow the joint to work normally and without any pain and stiffness. Almost all of us will develop osteoarthritis in some of our joints as we get older, though we may not even be aware of it.

However, the repair processes don’t always work so well and changes to the joint structure can sometimes cause or contribute to symptoms such as pain, swelling or difficulty in moving the joint normally.

For example:

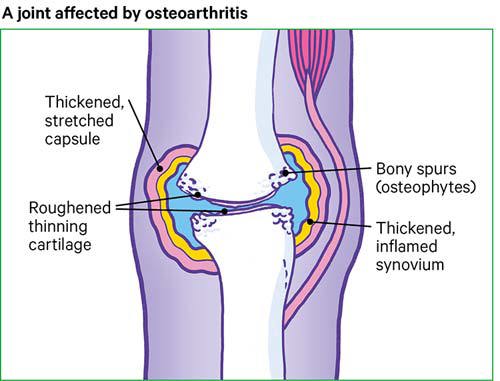

- Extra bone may form at the edge of the joint. These bony growths are called osteophytes and can sometimes restrict movement or rub against other tissues. In some joints, especially the finger joints, these may be visible as firm, knobbly swellings.

- The lining of the joint capsule (called the synovium) may thicken and produce more fluid than normal, causing the joint to swell.

- Tissues that surround the joint and help to support it may stretch so that after a time the joint becomes less stable.

Symptoms

The main symptoms of osteoarthritis are pain and sometimes stiffness in the affected joints. The pain tends to be worse when you move the joint or at the end of the day. Your joints may feel stiff after rest, but this usually wears off fairly quickly once you get moving. Symptoms may vary for no obvious reason. Or you may find that your symptoms vary depending on what you’re doing.

The affected joint may sometimes be swollen. The swelling may be:

- hard and knobbly, especially in the finger joints, caused by the growth of extra bone

- soft, caused by thickening of the joint lining and extra fluid inside the joint capsule.

The joint may not move as freely or as far as normal, and it may make grating or crackling sounds as you move it. This is called crepitus.

Sometimes the muscles around the joint may look thin or wasted. The joint may give way at times because your muscles have weakened or because the joint structure has become less stable.

Causes

It’s still not clear exactly what causes osteoarthritis. We do know it isn’t simply ‘wear and tear’ and that your risk of developing osteoarthritis depends on a number of factors:

Age

Osteoarthritis usually starts from the late 40s onwards. This may be due to bodily changes that come with ageing, such as weakening muscles, weight gain, and the body becoming less able to heal itself effectively.

Gender

For most joints, osteoarthritis is more common and more severe in women.

Obesity

Being overweight is an important factor in causing osteoarthritis, especially in weight-bearing joints such as the knee and the hip.

Joint injury

A major injury or operation on a joint may lead to osteoarthritis in that joint later in life. Normal activity and exercise don’t cause osteoarthritis, but very hard, repetitive activity or physically demanding jobs can increase your risk.

Joint abnormalities

If you were born with abnormalities or developed them in childhood, it can lead to earlier and more severe osteoarthritis than usual.

Genetic factors

The genes we inherit can affect the likelihood of getting osteoarthritis at the hand, knee or hip. Some very rare forms of osteoarthritis are linked to mutations of single genes that affect a protein called collagen. This can cause osteoarthritis to develop in many joints at an earlier age than usual.

Other types of joint disease

Sometimes osteoarthritis is a result of damage from a different kind of joint disease, such as rheumatoid arthritis or gout.

Two factors that may affect the symptoms of osteoarthritis, but aren’t a direct cause of it are the weather and diet:

Weather

Many people with osteoarthritis find that changes in the weather make the pain worse, especially when the atmospheric pressure is falling – for example, just before it rains. Although the weather may affect the symptoms of your arthritis, it doesn’t cause it.

Diet

Some people find that certain foods seem to increase or lessen their pain and other symptoms. However, your weight is more likely than any other specific dietary factors to affect your risk of developing osteoarthritis.

How will osteoarthritis affect me?

Osteoarthritis affects different people, and different joints, in different ways. But, for most people, osteoarthritis doesn’t continue to get steadily worse over time.

For some people, the condition reaches a peak a few years after the symptoms start and then remains the same or may even improve. Others may find they have several phases of moderate joint pain with improvements in between.

The degree of damage to a joint isn’t very helpful in predicting how much pain you’ll have. Some people have a lot of pain and mobility problems from a small amount of damage, while others have a lot of damage to the joint but few or no symptoms.

If you have severe osteoarthritis, you may find some of your daily activities more difficult depending on which joints are affected. More severe osteoarthritis can also make it difficult to sleep.

Which joints are affected?

Any joint can develop osteoarthritis, but symptoms linked to osteoarthritis most often affect the knees, hips, hands, spine and big toes.

The knee

Osteoarthritis of the knee is very common. This is probably because your knee has to take extreme stresses, twists and turns as well as bearing your body weight. Osteoarthritis often affects both knees.

The hip

Osteoarthritis of the hip is also common and can affect either one or both hips. The hip joint is a ball-and-socket joint which normally has a wide range of movement. It also bears a lot of your weight. Hip osteoarthritis is equally common in men and women.

The hand and wrist

Osteoarthritis of the hands usually occurs as part of the condition nodal osteoarthritis. This mainly affects women and often starts around the time of the menopause. It usually affects the base of your thumb and the joints at the ends of your fingers, although other finger joints can also be affected.

The back and neck

The bones of your spine and the discs in between are often affected by changes that are very similar to osteoarthritis. In the spine, these changes are often referred to as spondylosis. Although they are very common, they aren’t the most common cause of back or neck pain.

Read more about osteoarthritis of the spine.

The foot and ankle

Osteoarthritis of the foot generally affects the joint at the base of your big toe. However, osteoarthritis of the mid-foot is also quite common. The ankle is the least commonly affected part of the foot.

The shoulder

The shoulder consists of two joints, either of which can be affected by osteoarthritis:

- a ball-and-socket joint where the upper arm meets the shoulder blade – called the glenohumeral joint

- a smaller joint where the collarbone meets the top of the shoulder blade – called the acromioclavicular joint.

The elbow

The elbow joint isn’t commonly affected by osteoarthritis. When it is affected, it often follows either a single serious injury or a number of more minor injuries.

The jaw

The jaw, or temporomandibular joint, is one of the most frequently used joints in the body and the cartilage in this joint is particularly prone to wear. Osteoarthritis in the jaw often starts at an earlier age than in other joints.

Diagnosis

It’s important to get an accurate diagnosis if you think you have arthritis, as different types of arthritis often need very different treatments. The diagnosis of osteoarthritis is usually based on:

- your symptoms – how and when they started, how they’ve developed, how they affect your life, and any factors that make them better or worse

- a physical examination – your doctor will check for:

- tenderness over the joint

- creaking or grating of the joint – known as crepitus

- bony swelling

- excess fluid

- restricted movement

- joint instability

- weakness or thinning of the muscles that support the joint.

What tests are there for osteoarthritis?

There’s no blood test for osteoarthritis, although your doctor may suggest you have them to help rule out other types of arthritis.

X-rays aren’t usually helpful in diagnosing osteoarthritis, although they may be useful to show whether there are any calcium deposits in the joint.

In rare cases, an MRI scan of the knee can be helpful to identify other possible joint or bone problems that could be causing your symptoms.

Should I see a specialist?

It’s unlikely that you’ll need to see a specialist to get a diagnosis of osteoarthritis, although your doctor may refer you if there’s some doubt about the diagnosis or if they think there might be additional problems.

Your doctor may refer you if specialist help is needed to manage your osteoarthritis – this might be for physiotherapy, podiatry for foot problems, or occupational therapy, which can help if you’re having difficulty with everyday activities.

If your arthritis becomes severe and is causing long-term problems, your GP may refer you to an orthopaedic surgeon to consider joint surgery or to a pain management programme.

Managing symptoms

Although there’s no cure for osteoarthritis yet, there are treatments that can provide relief from the symptoms and allow you to get on with your life. These include:

- lifestyle changes

- pain relief medications

- physical therapies

- supplements and complementary treatments.

Physical activity

Many people worry that exercising will increase their pain and may cause further joint damage. However, while resting painful joints may make them feel more comfortable at first, too much rest can increase stiffness.

You shouldn’t be afraid to use your joints. If pain makes it difficult to get started with exercise, you could try taking a painkiller such as paracetamol beforehand. And if you feel you’ve overdone things a bit, try applying warmth to the painful joint – or if it’s swollen, applying an ice pack may help.

If you haven’t done much exercise for a while you might want to get advice from a physiotherapist. They’ll be able to help you work out a programme that works for you. The most important thing is to start gently and build up gradually.

You may want to give our exercises for healthy joints a try.

There are three types of exercise you should try to include:

Range of movement exercises

These exercises involve taking joints through a range of movement that feels comfortable and then smoothly and gently easing them just a little bit further.

Strengthening exercises

These are exercises performed against some form of resistance to strengthen the muscles that move and support your joints. You could use light weights, a resistance band or try exercising in water.

Aerobic exercise

This means any physical activity that raises your heart rate and gets you breathing more heavily. This type of exercise burns off calories, so it can help if you need to lose a bit of weight. It can also improve your sleep and help to reduce pain.

Walking, cycling and swimming are all excellent forms of exercise for people with arthritis. Or you could try an exercise bike or cross-trainer. Walking laps in the shallow end of a swimming pool is also great for strengthening leg muscles.

Hydrotherapy or aquatic therapy pools are warmer than normal swimming pools. The warmth is soothing and relieves pain and stiffness, while the water supports your weight but still offers some resistance for muscle-strengthening exercises.

Weight loss and diet

If you’re overweight, then losing even a small amount of weight can make a big difference to your symptoms – especially for weight-bearing joints (the hips, knees, back and feet).

The best way of losing weight is by following a healthy, balanced diet. Cut down on the number of calories you get from high-fat and sugary foods, but make sure that you’re including all the key food groups in your diet so you don’t miss out on essential nutrients. Gradually increasing how much physical activity you do will also help with weight loss.

There isn’t a specific diet that’s been proved to help with osteoarthritis. If you think a certain food might be making your symptoms worse then it’s best to test this by not eating the food for a few weeks and then reintroducing it. Be cautious about any diet that claims to cure arthritis or that suggests cutting out a particular food group completely.

There’s some research to suggest that oily fish, or oils produced from fish, may help with the symptoms of some forms of arthritis, especially rheumatoid arthritis. But increasing your intake of oily fish or taking a supplement might also be worth trying if you’re interested in using diet to manage osteoarthritis.

Medications

The drugs usually taken for osteoarthritis won’t affect the condition itself, but they can help to ease the symptoms of pain and stiffness.

NSAID creams and gels

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are available as creams, gels or patches that you apply directly to the skin. Ibuprofen and diclofenac gels are available over the counter at pharmacies and supermarkets. Others, such as ketoprofen, are only available on prescription. Creams, gels or patches work well for some joints, especially the knees and hands, but may not work as well for joints such as the hips, which lie deeper below the skin.

Paracetamol

Paracetamol is usually recommended as the safest type of pain relief tablet to try first. It’s best to take them before the pain becomes very bad. Paracetamol is readily available over the counter at pharmacies and supermarkets – and there’s no advantage in paying for more expensive brands.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

NSAID tablets are generally stronger pain-relievers than paracetamol. The most common is ibuprofen, which is widely available over the counter in pharmacies and supermarkets. You can try these for 5–10 days – if they haven’t helped after this time, then they’re unlikely to.

If you need them, your doctor may prescribe:

- higher doses of ibuprofen

- stronger NSAIDs such as naproxen or diclofenac

- a newer type of NSAID, such as celecoxib or etoricoxib, designed to reduce the risk of ulcers and bleeding in the gut.

If your doctor prescribes an NSAID, they’ll usually prescribe a drug called a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) as well to help protect the gut. Examples of PPIs are lansoprazole and omeprazole.

Stronger pain relief

If you find that paracetamol or NSAIDs don’t give good enough pain relief, you should speak to your doctor about other options. Your doctor may suggest using:

- paracetamol in combination with an NSAID. However, you shouldn’t take ibuprofen as well as a prescription NSAID.

- a drug such as co-codamol, which contains paracetamol and codeine. These are normally only used for very short periods because they have a higher risk of side-effects.

Steroid injections

Injections of a long-acting steroid may be given directly into a particularly painful joint, especially the knee or thumb. The injection often starts to work within a day or so and may improve pain for several weeks or months. Steroid injections are mainly used for very painful osteoarthritis, or for sudden, severe pain caused by crystals in the joint.

Other pain relief treatments

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS)

A TENS machine sends electrical pulses to your nerve endings through pads placed on your skin. It produces a tingling sensation and is thought to relieve pain by altering pain signals sent to the brain. The research evidence on the effectiveness of TENS is mixed, but some people do find it helpful. A physiotherapist will be able to advise on the types of TENS machine available and how to use them. Or they may be able to loan you one to try before you buy.

Hyaluronic acid injections

Hyaluronic acid, or hyaluronan, is a lubricant and shock absorber that’s found naturally in the fluid in your joints. Injections of hyaluronic acid have sometimes been used as a treatment for osteoarthritis of the knee. The treatment isn’t currently available on the NHS because research evidence on its long-term effectiveness is mixed. The treatment is, however, available privately.

Complementary medicine for osteoarthritis

Taking supplements

In many cases, there’s little research evidence to show that supplements and herbal remedies can improve arthritis or its symptoms, but many people feel they do benefit from them.

Below are a few of the supplements often used by people with osteoarthritis.

Glucosamine

Glucosamine is found naturally in the body in structures such as ligaments, tendons and cartilage. Supplements are usually produced from crab, lobster or prawn shells, although shellfish-free types are available. There’s some research to suggest it may have some benefit in painful osteoarthritis, especially of the knee.

Most trials have used a dose of 500 mg three times a day, and the evidence seems to suggest glucosamine sulphate may be more effective than glucosamine hydrochloride. It doesn’t help the pain straight away so you’ll need to take it for a couple of months. If it hasn’t helped after two months, then it’s unlikely that it will.

Chondroitin

Chondroitin exists naturally in our bodies and it’s thought that it helps give cartilage elasticity. The research evidence is limited to animal studies that suggest it might help to slow the breakdown of cartilage.

Don’t expect to see any improvement for at least two months. And if your cartilage is badly damaged, it’s unlikely that you’ll benefit from chondroitin.

Fish oils

Fish oils and fish liver oils are widely believed to be good for the joints. In fact, there’s not enough data available to say whether they’re effective for osteoarthritis, although there’s good evidence that fish oils can help with symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis.

Supplements made from fish livers often contain a lot of vitamin A, which can be harmful in large amounts. Supplements made from the whole fish usually contain less vitamin A, so are safer if you find you need a high dose of fish oils to get any benefit from them.

Complementary treatments

There are a number of different treatments available and they can generally be used alongside prescribed or over-the-counter medicines.

Some of the most popular therapies are listed here:

- Acupuncture claims to restore the natural balance of health by inserting fine needles into specific points in the body to correct imbalances in the flow of energy. There’s evidence that acupuncture is effective in easing some symptoms of osteoarthritis.

- The Alexander technique teaches you to be more aware of your posture and to move with less physical effort. There’s evidence that it can be effective for low back pain, though not specifically for osteoarthritis.

- Aromatherapy uses oils obtained from plants, which can be vaporised, inhaled, used in baths or a burner, or as part of an aromatherapy massage. There’s no research evidence that aromatherapy is effective for osteoarthritis symptoms, but some people find it helpful for relaxation.

- Massage can loosen stiff muscles, ease tension, improve muscle tone, and increase the flow of blood. A good massage can leave you feeling relaxed and cared for, though there’s only a little evidence that it’s effective in treating symptoms of osteoarthritis.

- Osteopaths and chiropractors manually adjust the alignment of the body and apply pressure to the soft tissues of the body. The aim is to correct structural faults, improve mobility, relieve pain and allow the body to heal itself. There’s a little research evidence that chiropractic is effective for spinal osteoarthritis. However, there’s no specific research evidence available on whether osteopathy is effective for osteoarthritis.

- T’ai chi is a ‘mind–body’ exercise designed to calm the mind and promote self-healing through sequences of slow, graceful movements. There’s good evidence that t’ai chi may ease osteoarthritis symptoms, particularly in the knee.

Finding a good therapist

Some therapies are available on the NHS, so it’s worth asking your GP about this. Private health insurance companies may also cover some types of therapy. However, most people pay for their own treatment, which can be costly.

Some therapies make bold claims – if you have any doubts, ask what evidence there is to back up these claims. The Institute for Complementary and Natural Medicine can help you find a qualified therapist.

Tell your therapist about any drugs you’re taking and speak to your doctor about the therapy you’re thinking of trying. Don’t stop taking prescribed drugs without talking to your doctor first and be cautious if any practitioner advises you to do so.

Surgery

Most people with osteoarthritis won’t need surgery, and it’s usually only considered once you’ve tried all other suitable treatments.

The options include:

- joint replacement surgery

- keyhole surgery techniques to wash out loose fragments of bone and other tissue from your knee – this is called arthroscopic lavage and is normally only available privately in the UK

- joint fusion – where the bones in a joint are fixed together surgically – this prevents movement of the joint, and therefore pain.

If you’re thinking of having surgery, take some time to find out what you can expect from it, what the possible risks are, and how you can best prepare for your operation and plan ahead for your recovery.

Information related to managing symptoms

-

Let's Move with Leon

Sign up to Let’s Move with Leon our weekly email programme of 30-minute movement sessions, presented by fitness expert Leon Wormley.

-

Let's Move

Sign up to Let’s Move to receive a wide range of content about moving with arthritis – from exercise videos to stories and interviews with experts – straight to your email inbox.

Tips for managing pain

Warmth and cold

Applying a hot-water bottle, wrapped in a towel to protect your skin, or a wheat-bag that you heat up in a microwave can help to ease pain. An ice pack, again wrapped in a towel to protect your skin, often helps to reduce swelling and discomfort. Ice can be applied for up to 20 minutes every couple of hours.

Splints and other supports

There’s a range of different splints, braces and supports available for painful joints. These can be particularly helpful if osteoarthritis has affected the alignment of a joint. It’s best to seek professional advice from an occupational therapist or physiotherapist before choosing one, so you can be sure it’s suitable for your needs.

Footwear

Choosing comfortable, supportive shoes can make a difference not only to your feet, but also to other weight-bearing joints including the knees, hips and spinal joints. In general, the ideal shoe would have a thick but soft sole, soft uppers, and plenty of room at the toes and the ball of the foot. If you have particular problems with your feet, then it’s worth seeing a podiatrist for more specific advice.

Walking aids

If your leg sometimes ‘gives way’ then a stick may help you feel less afraid of falling. When held in the opposite hand, it can also help to reduce pressure on a painful knee or hip. It’s best to get advice from a healthcare professional, as your reason for using a stick will determine which side you should use it on.

Posture

If you have arthritis, you’ll find that good posture can help to put less strain on your joints. When your posture is good, your body will feel more relaxed. Think about your posture throughout the day. Check yourself while walking, at work, while driving, or while watching TV.

Pacing yourself

If your pain varies from day to day, it can be tempting to take on too much on your good days, leading to more pain afterwards. Learn to pace yourself. If there are jobs that often increase your pain, try to break them down, allow time for rest breaks, and alternate with jobs that you find easier. Or think about other ways of doing a job that would cause less pain.

Living with osteoarthritis

Osteoarthritis can affect many different areas of your life, but there are things you can do to help reduce any problems it’s causing.

Managing at home

Depending on which joints are affected, there are lots of aids and adaptations to help you around the home, and some fairly simple changes can make a big difference.

If you’re not sure what’s available or how you might be able to reduce the strain on your joints, an occupational therapist will be able to advise you.

You may be able to get help with the costs of obtaining aids or having adaptations to your home. Eligibility varies depending on whether you live in England, Wales, Scotland or Northern Ireland. Wherever you live, the first step is to ask your local authority for a needs assessment.

In work or education

Most people with arthritis can continue in their jobs, although you may need to make some changes to your working environment, especially if you have a physically demanding job.

Speak to your employer’s occupational health service if they have one, or your local Jobcentre Plus can put you in touch with Disability Employment Advisors who can arrange workplace assessments.

Contact your local JobCentre Plus for information about Access to Work, a government initiative to help people overcome barriers to starting or keeping a job.

If you’re going into higher education, you may be eligible for a Disabled Students’ Allowance. The allowance covers any extra costs or expenses students have because of a disability. For more information, visit the Disability Rights UK website.

Public transport

Information is available on the National Rail website about station accessibility, train and station facilities, and assistance options. Transport for London offers similar information on their website and has produced a guide to avoiding stairs on the London Tube network.

Other local authorities and transport providers produce similar guides to accessible bus, train and minicab services, and some run their own transport schemes.

Caring for yourself

The emotional effects of arthritis can have just as much impact as the physical symptoms. Severe or long-term pain that affects your daily life and possibly disturbs your sleep can affect your mood. From time to time, your arthritis may get on top of you. If you’re feeling low, talk to your GP, who can signpost you to the appropriate services. You can also call our helpline on 0800 5200 520, who will listen and offer emotional support.

Possible complications

The changes in cartilage that occur with osteoarthritis can encourage crystals to form within the joint. These may be:

- sodium urate crystals, which can cause attacks of gout. The big toe is the most commonly affected joint.

- calcium pyrophosphate (CPP) crystals, which can also cause sudden severe pain and swelling. CPP crystals can affect any joint but are more common in joints already affected by osteoarthritis.

Research and new developments

Research is helping us to understand more about the causes of osteoarthritis, and to develop new treatments.

Our previous research has:

- highlighted the important role that exercise can play in reducing pain

- contributed to the approval for NHS funding of a treatment called autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI) that repairs small areas of damaged cartilage using healthy cartilage grown from your own cells

- identified a number of jobs linked with a higher risk of developing osteoarthritis.

Research we’re currently funding includes:

- a centre based in Oxford, which is looking at how osteoarthritis develops and aims to find new ways of predicting how it’s likely to progress

- a pain centre, based in Nottingham, which aims to improve our understanding of what causes pain so that better treatments can be developed

- a study into the part played by nerve proteins in and around the joints to find out if they could be a target for future pain treatments.

Mel's story

I was diagnosed with osteoarthritis in my knees and hands when I was 43.

I’d had some knee problems a few years before and I thought it was because I was standing all day in my job. It was worse when I woke up in the morning. The pain when I walked upstairs was excruciating. And with my hands it was terrible. I would struggle to do things like open doors, tie my laces or put the top on a bottle of water.

My doctor did blood tests and I was then referred to the rheumatology department at the hospital. The rheumatologist told me it was osteoarthritis. When someone tells you that you have arthritis, it’s awful. But I’m stubborn and determined. I won’t let arthritis determine what I can and can’t do.

I joined the gym in the March of 2014. It was obvious then that there were only certain things that I could go on, but I did a Pilates class once a week and that was good for flexibility.

I met Shane, a personal trainer at the gym I go to – I like Shane’s approach that if something hurts, you find something else to do. Even if you just wake up in the morning and walk to the shops at the end of the road, that’s ok. You can then walk a bit further over the course of a few days or weeks. After three weeks with Shane, I could already walk upstairs without any pain.

It’s tough, and it may take time, but it’s about making that first step. I wasn’t really exercising much before, but I couldn’t imagine not exercising now. Once I got started, I became curious about how much I could do. I find that if I don’t do anything, it starts to hurt more, because everything starts to stiffen. It can be a vicious circle; if I seize up, I find it harder to start exercising again!

As well as becoming more active, I decided to take a good look at what I was eating. I’ve drastically improved my diet. I started eating only good food and got rid of all the rubbish. I feel so much better. Even though I know how much I’ve improved, I still have arthritis and I know it’s there. I don’t take painkillers now, because I would rather be exercising and just go down that route.

Everyone’s different, but my advice would be to get out there and do something, anything, and just keep doing it. Set yourself realistic targets and just keep pushing yourself a little bit more.

Charles' story

Charles, 62, has lived with osteoarthritis for most of his adult life, having had problems with the tendons in his left leg since childhood. Over the last eight years he’s had both knees and his left hip replaced, but his positive approach and passion for swimming have helped Charles to keep doing what he loves.

Charles explains: "I’ve always been active; enjoying long walks, swimming and playing golf despite having good and bad days with the pain in my legs.

"In my 50s my knees got worse really quickly and it soon limited what I was able to do. But I’ve always kept on swimming, even during the difficult times when I’ve had to stop doing other things because of the pain."

Swimming to live well

Charles credits swimming with playing a vital role in helping him to live well with arthritis, saying: "Swimming has helped me in so many ways. I’ve no doubt it played a big part in delaying the inevitable when it came to having my joints replaced. I wanted to hold off on the operations as long as possible and because swimming is non-weight bearing I could keep my knees moving even on bad days.

"It’s also meant I’ve been more physically prepared for the operations and has helped me to have a speedy and full recovery each time."

"Swimming is the key thing I do to keep my knees and hip as healthy as possible. It’s very important psychologically as well. I won’t deny some mornings it’s a chore getting up and going to the pool, but I always feel so much better for it. After I’ve been for a swim, I feel great and I think ‘I have done something today’. It lifts you.”

Fourteen weeks after his most recent operation, Charles is back at work for the National Trust, playing golf, walking in Derbyshire with his wife Karen and, of course, swimming twice a week. He explains: "I love life, so I'm determined to make my new knees and hip last as long as possible and to get the most out of them. Swimming is a big part of making that happen.

"If it wasn’t for swimming my life wouldn’t be as complete as it is. I wouldn’t be able to do everything I enjoy."

"If anyone living with arthritis is thinking of trying swimming, I’d say give it a go. It might not be easy at first, but it gets easier and the benefits are huge. You’ll be able to live a fuller life and you’ll smile more!"